Black Farmers in Texas Part III

by Benjamin Brown

Black land loss ranked among the most pressing civil rights issues of the late 20th century, and yet it remained largely unaddressed in the sphere of public policy. Andy Welch described the Hightower Texas Department as the coming of a bright new day.

“The Hightower election and administration was a big wake up. … The Texas Department of Agriculture, until 1983, existed to serve the good ‘ol boys. … But now, they might get an memo saying it’s family land heritage time, we need y’all beating the bushes to find people that we can recognize as a heritage farm. Or, maybe, we’re going to be down here having a black farmer conference, so you need to get out into the black churches with fliers and information to make sure they know about this. … That was a major cultural shift for the good ‘ol boys.”

The Hightower effort did not manifest from thin air, nor did the TDA act unilaterally. The “cultural shift” it advanced was ancillary to the grassroots movement headed by figures like Cather Woods and Barbara Lange. As Woods explained to PHIT, “Black landowners have lost so much property. And all of it wasn’t a lack of a payment; a lot of it was … [that]somebody that didn’t know their rights, and they could very easily lose what they have. … To access some of the programs that USDA had, you had to go in groups. And that’s why the Landowners’ Association, Texas Small Farmers and Ranchers, and 100 Ranches were formed: knowledge is power.”

Barbara Lange, executive director of the Landowners’ Association, expanded on that point, saying, “If you want to acquire [land] or had acquired it through inheritance of a property or … you went out and bought it, we wanted to keep it off the courthouse steps. The only way you could keep it off the courthouse steps was to make it productive. … It’s got to be a business.” The TDA partnered with activist organizations to organize conferences on land retention. Lange continued: “If you remember one thing, it’s the educational part. We talked about taxes. We talked about tax credit. We talked about funding, we talked about developing. We had workshops on the most productive way of utilizing the land or the most productive way of growing fruit trees, or growing tilapia and those kinds of things.” TDA officials proved especially helpful in knowing “…where to go find specialists. There’s so many different entities, you got to know something about. If you don’t know where to go find a specialist, you’re up a creek without a paddle.”

Gus Townes, Hightower’s Director of Direct Marketing, described the conferences as fulfilling a dual purpose: “We saw these sessions as an opportunity to reach out to farmers who may not be aware of the various TDA programs available to them. But we didn’t want to just let these farmers know about TDA and its programs. We also wanted them to know that TDA is ready to listen to their concerns and help them in their efforts to find solutions to their specific agricultural problems.”

Even Lange’s private educational efforts were complemented by connections at the TDA: “We worked very closely with the Texas Department of Agriculture and had wonderful friends who kept us abreast of what was going on, who talked to us constantly about the farm bill, NRCS, and conservation and all those kinds of things. We were constantly involved on that level and shared that kind of information directly through our educational program.”

Beyond the realm of pure policy, the Hightower TDA did much to assuage the mistrust many African Americans felt towards the government. Cather Woods noted that Hightower “worked hard to make sure that he made it better for blacks. By making sure that you knew what was there, by reaching out to the various committees, by bringing in people of color into his organizations. Because yourself, if you see that somebody looks like you, then you will trust the head more than you would if nobody there looked like you. That was one thing he was famous for: inclusion.”

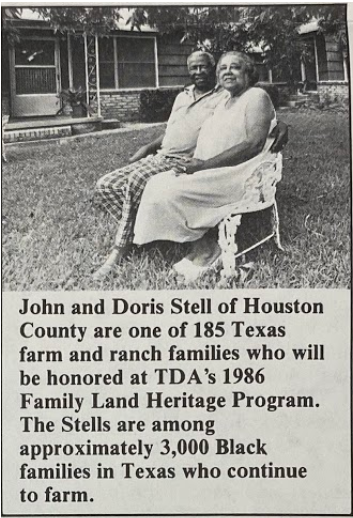

The TDA also made an effort to highlight the legacy of black farming in Texas. Take, for instance, the Stell family of Houston, who were featured in the Department’s Family Land Heritage Program. While the practice of celebrating historic farms was not unique to the Hightower administration, its approach differed in celebrating those who “have resisted not only nature’s pressures, but also social pressures,” to quote Hightower directly. In speaking of the Stells, he said they “are one of approximately 3,000 Black families in Texas who continue to farm despite the steady decline in the number of Black farmers.”

In sum, it is best to understand the Hightower administration as a critical ally, not a single-handed savior, in the fight to save Black agriculture. It positioned itself within a broader patchwork of activist organizations committed to racial justice, lending institutional assistance to a grassroots effort.