Black Farmers in Texas

by Benjamin Brown

Part 1

In 1973, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz rendered clear his approach to farm policy: “get big or get out.”

It marked the latest episode in a century-long feud between Wall Street and the Main Street of agrarian America. In the wake of the Civil War, the federal government pursued a series of measures designed to improve the nation’s macroeconomic woes. Chief among these changes was the re-institution of the gold standard, which benefitted banking elites at the expense of small farmers. This accompanied a broader shift of family farming away from subsistence agriculture and towards cash crops. The corporate orientation of federal policy hurt small producers, who faced falling prices and a monetary supply incapable of financing their operations.

In 1892, a coalition of disgruntled farmers convened in Omaha, Nebraska, to found the Populist Party, penning a manifesto which promised “to restore the government of the Republic to the hands of ‘the plain people.’” The Populists would enjoy limited electoral success, but their ideas would help re-frame American agricultural policy around an egalitarian ethos. The New Deal would inaugurate a farm economy that privileged the small producer above corporate agribusiness. A system of production controls and price supports meant to keep small farmers solvent stood at the center of FDR’s program.

However, the postwar period brought an assault on the liberal framework of the preceding decades. Starting under President Eisenhower, and continuing into the Nixon and Reagan administrations, the U.S. Department of Agriculture tipped the balance of power back towards agribusiness, incentivizing over-production to lower prices and bolster American competitiveness in international markets. Small-scale family farming, which was already slipping into the dustbin of history, began a precipitous fall. In the early ‘80s, Texas alone saw 173 farm foreclosures a week.

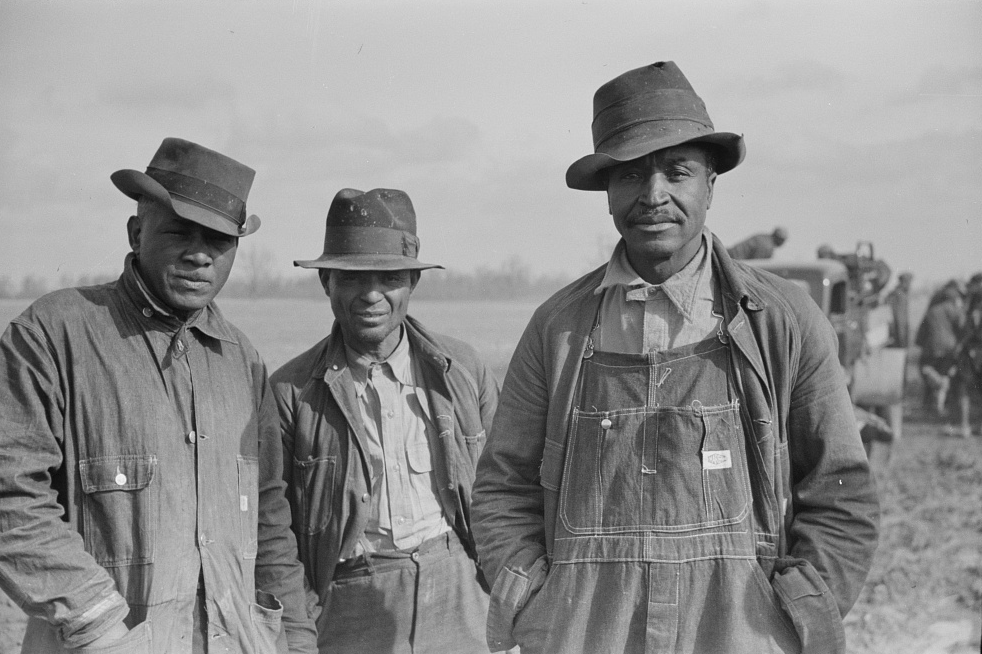

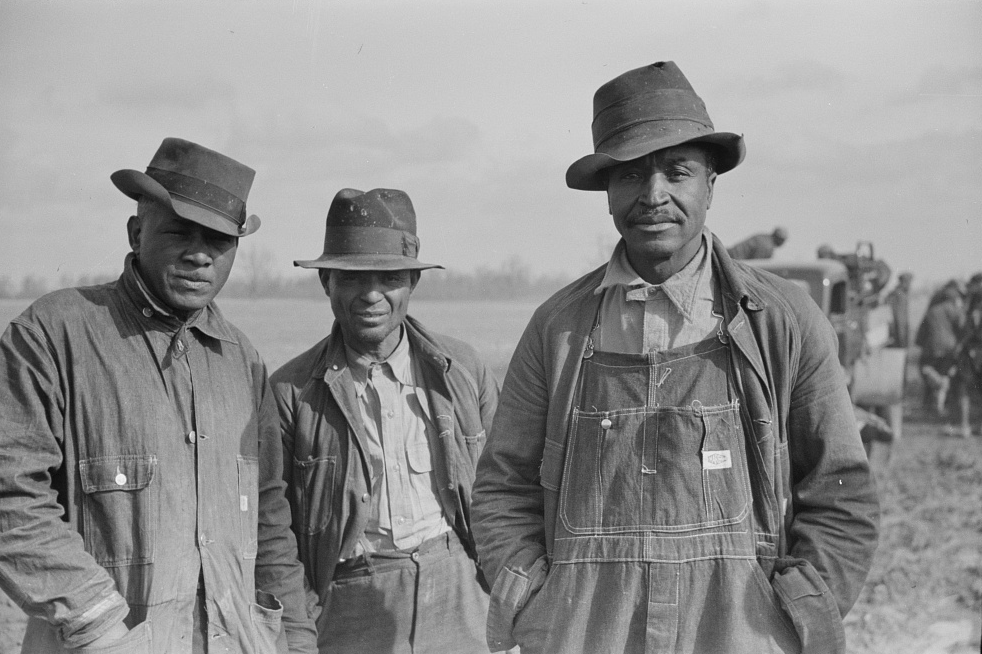

No demographic felt the dismal trend harder than African Americans. Dr. Debra A. Reid, notable for her work on black farming, explored the racial contours of family farm decline in her African Americans and Land Loss in Texas. In her words: “In the 1980s, stories of the passing of the ‘family farm’ were common in the media. While the trend toward larger and fewer farms affects rural Americans regardless of race, blacks have been hit harder than other groups … Many of the ways that a farm can ‘go under’ are similar across racial lines, [but] there are some more specific and interrelated reasons for land loss among African-American farmers. They include failure to write a will, failure to pay property taxes, non-participation in government programs, and racism.”

Enter Jim Hightower, the self-described “agrarian populist” who headed the Texas Department of Agriculture throughout much of the 1980s. His progressive politics revolutionized the TDA, turning “…the once-obscure, $20-million-a-year, 580-person Agriculture Department into a national center for reforming American farm policy.”

His approach to remediating the family farming crisis was bipartite. First came the grander corrective effort, which targeted the problem indiscriminately. A New York Times profile outlined Hightower’s effort to “…institute controls on production … determined by domestic and international demand. … There would be no surpluses, thus no Government payments to farmers producing surplus crops and no costs to store them.” The Department experimented with methods of stimulating rural Texas, which David Guarino described as being in the throes of a “localized Great Depression.” As young people fled their parents’ credit-starved farms, the Hightower TDA introduced a loan guarantee program for family producers. Bill Magness spoke to PHIT about Department-organized farmers’ markets, which existed “…as a way to try to cut out the middleman and bring the agricultural product to consumers,” the objectives being “…to aid the cause of small farmers” and, according to Gus Townes, “revive rural towns.”

The second dimension of the remediation program concerned black family farms, which carried unique challenges. In the words of civil rights activist Barbara Lange, “African American land was winding up on the courthouse steps” for reasons beyond the farm crisis. The USDA maintained a particularly contentious relationship with Black communities, facing civil rights lawsuits as recently as 1999 for discriminatory practices. Dr. Al Parks explained to PHIT how this mistrust, combined with the trauma of slavery, has exacerbated the decline of African American family farming. Many black families have lost their land through ignorance of their rights or apprehension towards USDA aid programs. The Hightower TDA sought to foster trust with conferences aimed at the “acquisition, retention, and production” of black land, to quote Lange. Figures such as Cather Woods worked with TDA, in conjunction with the efforts of black farmers’ organizations, to form a legal “shield” against land seizure. By the end of the 1980s, Texas stood out as a state that had reversed trends in black land loss.