General Patrick Cleburne and Confederate Emancipation

General Patrick Cleburne

Random Meditations at Random Museums

PHIT’s new project is to visit small Texas museums and tell stories of peculiar and little known episodes in Texas History. It is modeled somewhat on the Mysteries of the Museum, but we don’t want to get sued, so we changed the name to Meditations at the Museum.

The Johnson County Historical Museum is located in Cleburne, in the County Courthouse. The Johnson County Courthouse is truly one of the finest courthouse reconstructions around. Beautiful marble rises four stories around a central court. Faces of creatures can be seen peering through the marble. You have to see it to believe it.

The Museum is on the second floor and is nicely arranged although clearly it is a volunteer and an underfunded affair. While circling the exhibits, PHIT found a note in a cabinet devoted to General Patrick Cleburne, a confederate general who is the town’s namesake.

Cleburne was born in Ireland, and he fought in the British Army before migrating to Arkansas. He signed up to fight on the Confederate side in the Civil War, and proved to be a brilliant tactician. He was known as the Stonewall of the West. After the war, a group of his soldiers settled in Johnson County, Texas, and pressed to have the county seat named after their commander.

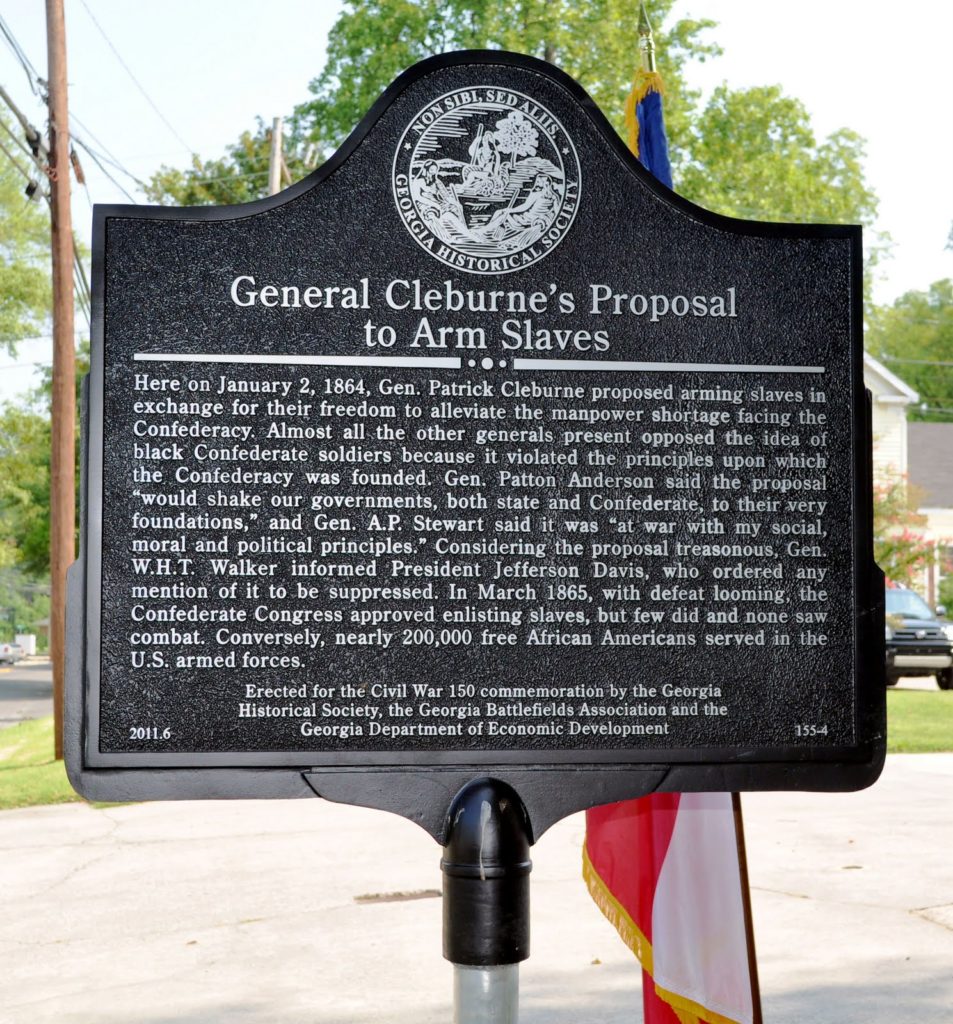

In the exhibit dedicated to the town’s namesake, there was a small quote from Cleburne. In late 1863, Cleburne advocated a unique policy to win the war. “Free the slaves and arm them.”

DUH! That is some serious thinking outside the box. The logic was inexorable. Free the slaves and what’s the point of fighting. Of course, it goes without saying that the proposal was rejected and Cleburne was ordered to not talk about it. He was killed in Battle of Franklin later in 1864.

HIs proposal gave me great mirth the rest of the day. Talk about cognitive dissonance. What did he think he was fighting for?

But it turns out the proposal wasn’t so off the wall. It was actually quite well thought out and sophisticated, clearly the product of a brilliant tactician. Cleburne basically prefigured in 1863 the ultimate Reconstruction adaptation to the victory by the North.

In late 1863, the South was clearly losing the war. The generals knew that they didn’t have the manpower. They had drafted every white male Southerner of fighting age. No one was left. Except male slaves. The only route to victory was to arm them. Offer them their freedom. And put them on the front lines.

It was an existential moment for the South, or at least it was to those who bothered to think about the implications.

By freeing slaves and keeping the North at bay, the South would get to keep their institutions. If they won the war, then they didn’t have to submit to the North. They were worried that Abe Lincoln really would give all the land, all the plantations, to the former slaves.

By 1863, those who bothered to think about it understood that the slaves were gone. Slavery was done. But if the South wanted to be in control of their own destiny, the south should free the slaves. Freedom didn’t mean they got the right to vote. Freedom didn’t mean that African-Americans had the right to control their lives.

Cleburne was Irish. He knew that the Irish were free, but the English still controlled everything. He understand that you can be free and not free at the same time.

Debate about Confederate Emancipation raged for rest of the war. Until the end, actual slaveowners said “No Way!” Cleburne’s gambit might have worked in 1863, but, by the end, when Confederate Emancipation was actually enacted in early 1865, the south worried, with good reason, that blacks would turn the guns on the slave owners.

“They day they give us guns, that the day the war ends,” said one slave in Georgia.

Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves by Bruce Levine is an excellent book that details this existential crisis in the South. As one of the Southern generals said during the discussion of Cleburne’s proposition, “If we arm the slaves, and they fight well, then everything we have said about the capacity of the Negro for the last 60 years is wrong.” Basically, he was admitting that if this gambit proved successful, his whole concept of how the world worked was wrong. Talk about an existential moment!

On another note, one major gripe about the Cleburne museum is that the Populist Party had its origin in Cleburne. During a major convention held in the town, the Alliance split into two factions, one of them political—they issued the Cleburne Demands in 1886. It was this platform that led to the creation of the Populist Party. There is not one word of mention of this major historical event.